October 13, 1775, will mark the 250th birthday of the United States Navy. As we look forward to commemorating this important anniversary, we should also remember that South Carolina’s independent navy was also born in 1775, roughly three months before the formation of the Continental Navy.

By Rob Shenk

As tensions with Great Britain continued to escalate, Charleston and the Lowcountry grew increasingly concerned about their maritime vulnerability. Not only was the Lowcountry’s economy heavily dependent on shipborne trade, but many of the colony’s most significant cities were also highly vulnerable to naval bombardment or amphibious attack. The menacing presence of the 343-ton Tamar (16-guns) and Cherokee (6-guns) in and around Charleston Harbor was a constant reminder of the Royal Navy’s ability to disrupt trade and threaten the city. Exacerbating the sense of coastal vulnerability was the news of the Royal Navy’s destruction of Charlestown, Massachusetts, in June of 1775 and the burning of Falmouth (today’s Portland, Maine) in October by Royal Navy warships. Would a rebellious Charleston be next? Many of Charleston’s more panicky residents had already decided to leave town.

While its delegates to the Second Continental Congress in Philadelphia debated the merits of creating an independent Continental navy, South Carolina’s Provincial Congress – its increasingly independent governing body – took action to improve its naval defenses.

July 1775: Birth of South Carolina’s Independent Navy

South Carolina’s Council of Safety – the body focused on defense matters – armed and equipped two large barges in Beaufort in early July 1775. These two barges, one crewed with six men and the other with nine, were to proceed down to Bloody Point, near the mouth of the Savannah River, to intercept an expected shipment of British gunpowder. The barges, commanded by Captains John Barnwell and John Joyner, met up with the Liberty, a Georgia schooner, on July 7, 1775. The following day, this small flotilla then confronted the British supply ship and its consort, the Royal Navy armed schooner Phillippa (6-guns) as they prepared to travel down the Savannah River. Ordered to anchor off of Cockspur Island, the British ships on July 9, 1775, were soon surrounded by rowboats filled with South Carolina Provincial soldiers from nearby encampments. Now in control of the British ships, the Patriots removed seven hundred weight of lead bullets, Indian trading muskets, lead bars, and 16,000 pounds of precious gunpowder from the supply ship. Four thousand pounds of that powder was subsequently shipped to George Washington’s gunpowder-starved army outside of Boston – an early and notable act of southern support for the Patriot forces in the north.

Commerce Captures the Betsy

Following up on the successful operation at Bloody Point, the Council of Safety then ordered that the merchant sloop Commerce be converted into an armed vessel. Captained by Clement Lempriere, an experienced mariner, shipbuilder, and former privateer from nearby Mount Pleasant, the Commerce was ordered to sail to the Bahamas and seize gunpowder held in Crown-controlled magazines around Nassau harbor. As the Commerce approached the waters off St. Augustine, Florida, it intercepted the Betsy, a British ship carrying a significant load of gunpowder. Instead of using the Commerce‘s guns, Captain Lempriere was able to “persuade”, some say bribe, the Betsy’s crew to surrender its 11,000 pounds of gunpowder. Shortly after the ship returned to Charleston, Commerce was released from service and its crew returned to shore.

Rising Tensions in Rebellion Road

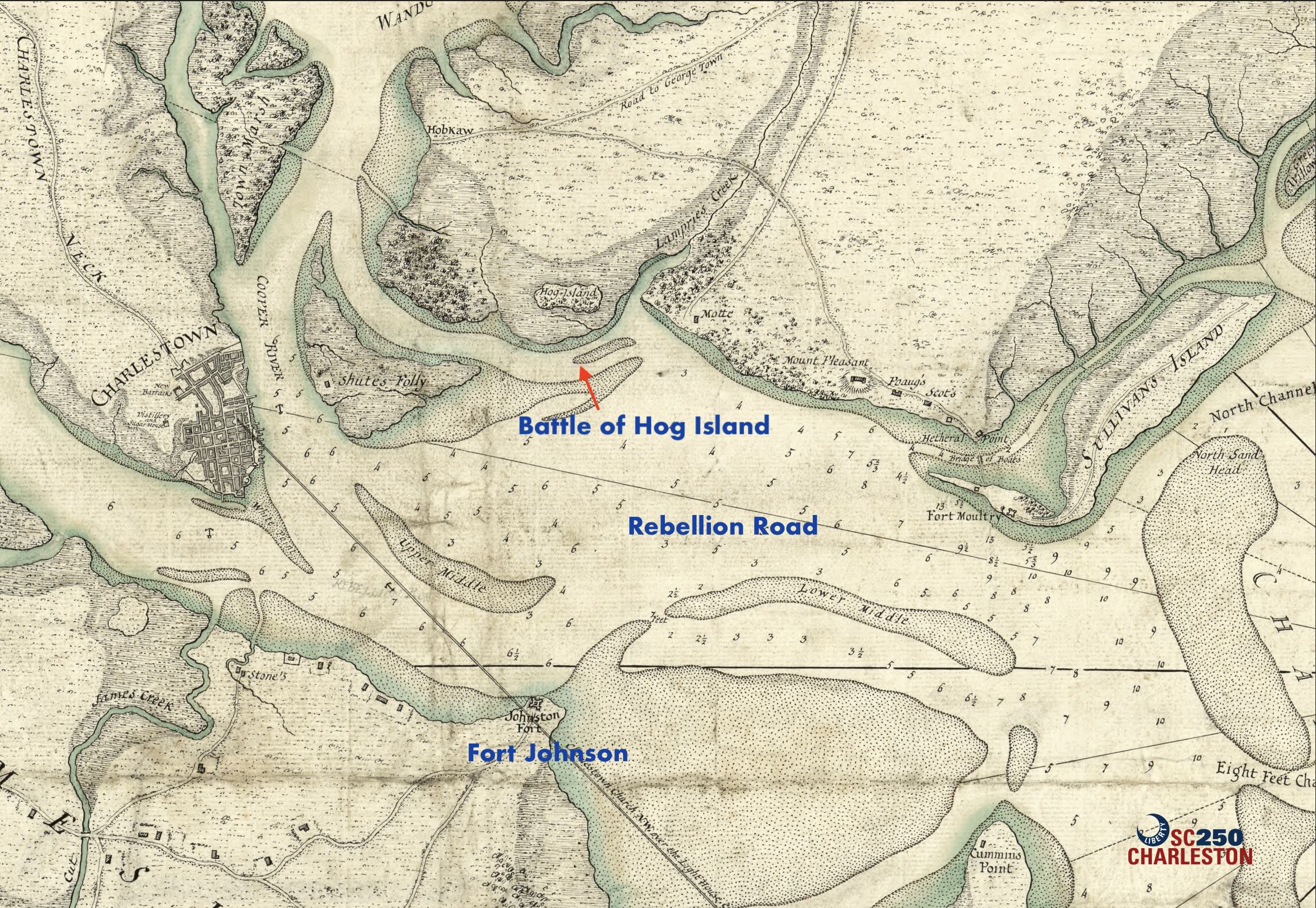

Convinced that it needed more ships for its infant navy, the South Carolina Provincial Congress on September 4, 1775, passed a resolution that would arm three schooners for coastal defense. And on September 15, 1775, South Carolina’s Royal governor, Lord William Campbell, fled his residence at 34 Meeting Street in Charleston and moved aboard the Tamar. From this warship in Charleston Harbor, Campbell would continue to direct actions against the growing rebellion. And to the Patriots’ great frustration, Loyalist forces onshore would continue to provide food and supplies to these British warships prowling Rebellion Road.

Tensions continued to mount throughout September 1775. On the same day that Lord Campbell moved to the Tamar, the Council of Safety ordered the immediate seizure of Fort Johnson. Fort Johnson was a fort that commanded the ship channel leading to Charleston’s wharves. 150 men from the 2nd South Carolina rowed over to the fort on James Island and took possession of the abandoned position. After taking one British gunner and four other men as prisoners, the men from Col. William Moultrie’s regiment raised their distinctive blue flag over the fort. On the 17th of September the Tamar and a small ship named the Swallow, sailed close to the fort and an engagement was expected. Despite the show of British force, the two ships sailed back to their anchorages in the harbor.

New Warships: Defense and Prosper

On October 13, 1775, South Carolina’s Council of Safety commissioned its first true warship, Defense. The Defense was a converted merchant ship equipped with 12 cannons. Simon Tufts, a transplanted New Englander, was named captain of the Defense and was ordered to intercept Royal Navy surveillance and supply vessels operating near Charleston’s shores. With most merchant ships now prevented from leaving the harbor, the Defense was able to secure a crew from mariners now stranded onshore.

Determined to add more ships to its rolls, the Prosper, a British merchantman in Charleston Harbor, was seized by the Council of Safety and converted into a 20-gun warship. Clement Lempriere, formerly the captain of the Commerce, was given command of this new warship. Manning this second new warship encountered a problem that would continue to vex the Patriots in Charleston – there were just not enough qualified sailors available for these ships. As a partial remedy, Colonel William Moultrie was ordered to send aboard the Prosper “…a detachment of forty Privates, who are best acquainted with maritime affairs.”

Both the Defense and Prosper were bigger and more heavily armed warships than the Royal Navy’s Tamar and Cherokee. However, despite their size advantages, the Royal Navy’s tars aboard the British warships were far more experienced in naval operations and combat than the Patriots.

As both sides adopted a more militant pose, a stream of letters exchanged between Lord Campbell, Captain Edward Thornbrough of the Tamar, and Patriot leaders onshore claimed, “unprovoked insults”, the “grossest misrepresentations,” and words “unbecoming the pen of a gentleman.” In a letter dated November 3, the Provincial Congress warned Thornbrough “that we are not destitute of means enabling us to take vengeance, for any violence you may think proper…” And on November 9, 1775, Congress declared that “we thus think it proper to warn you from an approach that must be productive of the shedding of blood….”

South Carolina’s First Battle of the War: The Battle of Hog Island

On November 11, 1775, the tensions between the opposing naval forces in Charleston Harbor finally erupted into direct, open combat. The Defense had been ordered to sink four sand-filled ships in Hog Island Channel – a likely avenue of approach for British warships threatening the town. Joining Captain Simon Tufts aboard the Defense was William Henry Drayton, president of the Provincial Congress and one of the more militant Patriots. As the Defense prepared to sink each of the hulks in the channel, the Tamar and Cherokee sailed towards the scene. Recognizing what the Defense was doing, the Tamar, with Royal Governor Campbell onboard, fired six rounds from its guns at the Defense, and the Patriot warship, with its heavier guns, returned fire on the two Royal Navy vessels. Both sides continued to exchange fire throughout the day with little effect. Around seven o’clock the following morning, the Defense sailed away, having sunk three of the four ships in the channel. The fourth was seized by a boat from the Tamar and towed away from the strategic channel. As reported in The South Carolina Gazette, the Defense had suffered “…one Shot under [its] Counter, one in [its] Broadside, and a third which cut [its] Fore Starboard Shroud. Not a Man was wounded!”

Despite the lack of casualties on either side, William Henry Drayton, participant in the battle, declared that “the actual commencement of hostilities by the British arms in this colony against its inhabitants, is an event of the highest moment to the southern part of the United Colonies…”

While the Battle of Hog Island had indeed been the first battle between the Patriots and British in South Carolina, both sides made a conscious effort to avoid further combat after the battle.

In November, the South Carolina Provincial Congress took two more notable steps to bolster its naval strength. First, the Congress brought into service two pilot boats – the Eagle and Hibernia. These small boats, positioned in the Stono River, were tasked with the mission of alerting inbound merchant ships to avoid heading into Charleston and to seek other ports free of Royal Navy warships. Secondly, the Congress also created a navy department headed by Edward Blake, a man well-experienced in maritime trade.

Learn More: The Battle of Hog Island

Scorpion and Comet

As 1775 came to a close, both sides sought to strengthen their naval forces. The Royal Navy 10-gun sloop Scorpion appeared off Charleston harbor at the end of November and soon captured two inbound schooners. Trade in and out of Charleston had come to a veritable standstill. The South Carolinians soon added the Comet to its forces. This converted brigantine was armed with twelve to fourteen guns. To help secure enough qualified sailors for the Comet and other ships, the Provincial Congress sent Robert Cochran to Massachusetts to recruit up to 300 men.

Yet unknown to the South Carolinians, King George III approved the American Prohibitory Act on December 22, 1775, which banned “all manner of trade and commerce” in America. The act declared that any vessels captured by the Royal Navy after January 1, 1776, would now be considered lawful prizes. When news of this act reached Charleston in March of 1776, one Patriot leader remarked that “the People of South-Carolina look on the late act of Parliament as a declaration of war.” And certainly, war is what Charleston would face in June of 1776 when Sir Peter Parker’s fleet reached the Charleston Bar, intent on taking control of Charleston harbor for good.

References

Charleston’s Maritime Heritage, 1670-1865, an illustrated history by P.C. Coker III

Defense, A Vessel of the Navy of South Carolina by Harold Mouzon, The American Neptune, Volume XIII, No. 1, 1953.

The Ship “Prosper,” 1775-1776 by Harold Mouzon, The South Carolina Historical Magazine, January 1958, Vol. 59, No. 1

The South Carolina Gazette, November 14, 1775

Extracts from the journals of the Provincial Congress of South Carolina held at Charles-town, November 1st to November 29, 1775, Published by order of the Congress, 1776.

Bloody Point, July 9, 1775, Carolana.com. https://www.carolana.com/SC/Revolution/revolution_bloody_point.html

“A SPIRIT OF ENTERPRIZE IN TRADE, SUPERIOUR TO ANY OTHER STATE”: COMMERCE IN WARTIME CHARLESTON, 1775-1780 by David Huw, The South Carolina Historical Magazine, Vol. 118, No. 4 (October 2017)

The Fate of the Ship “Prosper”, by Thurman Morgan, The South Carolina Historical Magazine, Jul-Oct 1992, Vol. 93

History of Fort Johnson: One of the Defenders of Charleston Harbor by Mark Maloy, American Battlefield Trust. https://www.battlefields.org/learn/articles/history-fort-johnson

Fort Johnson #1 – September 15, 1775 – Carolana.com: https://www.carolana.com/SC/Revolution/revolution_fort_johnson_1.html

The Navy of the American Revolution by Charles Oscar Paullin, Chicago 1906

William Henry Drayton to the Georgia Council of Safety, Savannah, November 12, 1775

_________________________________

Rob Shenk is a board member of SC250 Charleston, a local non-profit established to support commemorative events and educational programs in the Charleston area, and is the Chief Content Officer for Wide Awake Films, a leading producer of history-centered films and museum interactives. Rob previously held senior executive positions at George Washington’s Mount Vernon and the American Battlefield Trust.