On November 11-12, 1775, Royal Navy ships engaged the schooner Defense in the Battle of Hog Island – the first battle of the Revolutionary War in South Carolina.

By Benjamin Schaffer, Ph.D.

On 12 November 1775, the South Carolina Patriot leader William Henry Drayton wrote to his compatriots on the Georgia Council of Safety to inform them that “The actual commencement of hostilities by the British arms in this colony against the inhabitants, is an event of the highest moment to the southern part of the United Colonies on this continent.”1 What Drayton was referring to was not a land battle or lengthy siege, but an inconclusive naval engagement in Charleston Harbor between the crews of the South Carolina Navy schooner Defence, and two Royal Navy sloops: Cherokee and Tamar.

Although Drayton contended this naval battle was the true start of the war in South Carolina, and an event of the “highest moment” for the entire South, it has sadly been forgotten by generations of Americans. A number of factors have contributed to this amnesia, ranging from the inconclusiveness and relatively bloodless nature of the battle, indifference towards the naval theatre of the American Revolution, and most importantly, our state’s greater interest in the story of the American victory over the British Royal Navy at Fort Moultrie in June of 1776. However, by reexamining this obscure battle as we near its 250th anniversary, we have the opportunity to revisit the pivotal early months of the conflict from the perspectives of well-known Founding Fathers, Royal Navy and South Carolina Navy Officers, and a diverse array of free and enslaved mariners. The Battle of Hog Island Creek was no mere South Carolina skirmish, but the earliest salvo in the Southern colonies of the Revolutionary Battle of the Atlantic.

Strategic Background

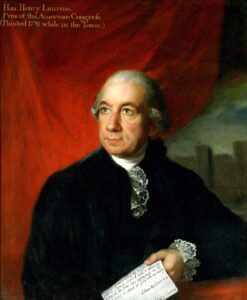

In the early months of 1775, Whig leaders in Charles Town were aware of the increasing likelihood of war between the American colonies and the Crown. Like many other colonies, they organized a temporary regional government to handle this increasingly volatile situation. The Provincial Congress, led by President Charles Pinckney, handled legislative affairs like earlier colonial assemblies. Much of the actual executive and daily authority of government, however, was left in the hands of a thirteen-member Council of Safety, led by the powerful planter and politician Henry Laurens. Even before news arrived of the first battles at Lexington and Concord in April of 1775, a “Secret Committee” of those political leaders, led by William Henry Drayton, planned a series of increasingly militant acts, including the seizure of the provincial armory. 2

While these acts were certainly ‘revolutionary,’ the provincial government’s formation of several regular infantry regiments–and even a state navy–in the summer months drew on more than a century of local military experience. For decades, South Carolina provincial naval vessels and land-based militias had served alongside British forces in sundry battles against French, Spanish, Native American, and piratical enemies. Now, for the first time, that military experience would prove vital in combating British forces themselves. 3

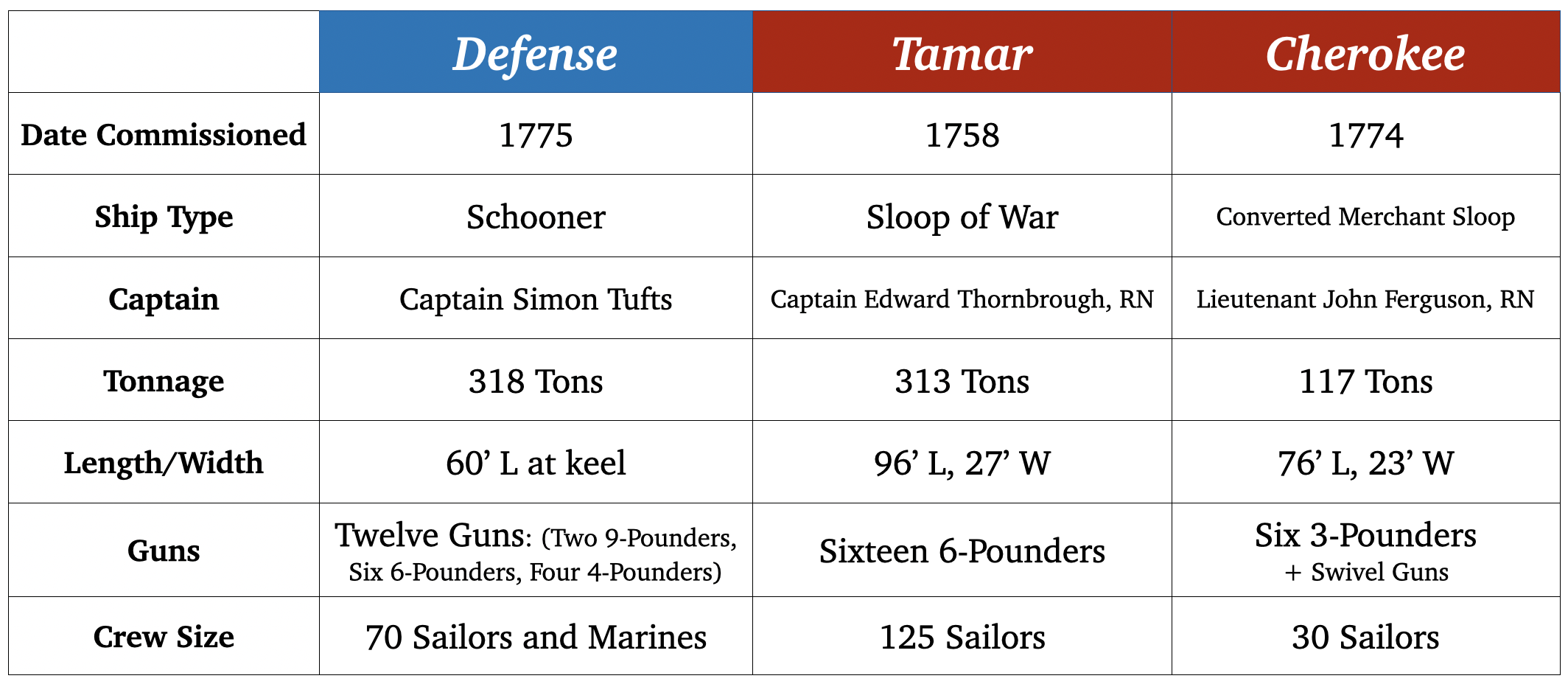

Throughout July and August, South Carolina authorities (both independently and in collaboration with their counterparts in Georgia) organized various maritime missions to seize gunpowder from British ships in Georgia and Florida. 4 However, none of these expeditions–including the audacious capture of Fort Johnson, on James Island–secured the harbor from the last bastions of British power in the colony: the Royal Navy vessels Tamar and Cherokee. 5 A description of these vessels, commanded by Captain Edward Thornbrough and Lieutenant John Ferguson, respectively, is important to better understand the anxiety that gripped local officials.

Broadly speaking, neither royal vessel was a large frigate, but their combined firepower allowed the duo to control access to Charles Town harbor. Cherokee was a former merchant sloop, with a burthen (i.e. cargo carrying capacity) of 117 tons, a length of seventy-six feet, a breadth of twenty-three feet, a complement of thirty sailors, and a relatively small armament of six three-pounder guns and sundry swivel guns. 6 Far more fearsome was Tamar, a well-armed sloop-of-war. Unlike the small, single-masted Bermuda sloops favored by pirates and privateers of earlier decades, sloops-of-war were three-masted vessels that combined the versatility and speed of lighter vessels with the firepower of larger Royal Navy warships. Tamar was over ninety-six feet in length, twenty-seven feet in breadth, and had a burthen of 313 tons. She was designed to have a complement of 125 sailors and was armed with sixteen six-pounder guns (outside of her swivel guns). 7

Unfortunately, the colony’s government couldn’t muster any vessels of that force. Nevertheless, in early September, the Council of Safety planned to fit out and arm three civilian schooners, the first of which would be called Defence. 8 With two large masts rigged in a ‘fore-and-aft’ pattern (i.e. designed with sails parallel to the deck), and with slightly raked and sleek decks, schooners were swift coastal vessels that usually had burthens of under fifty tons. 9 Command of Defence was given to an experienced New England merchant captain and long-time Charles Town resident, Simon Tufts. By early November, Defence would have a complement of over seventy sailors and ‘marines’ from a local infantry regiment, and would be armed with twelve guns (four four-pounders, six six-pounders, and two nine-pounders).10 When one calculates the broadsides each side could fire at one another, the Defence was slightly outclassed by her British foes.

From the cabin of the smaller Cherokee, Lord William Campbell–a Royal Navy veteran, the last royal governor of the province, and recent refugee–attempted to take control of a quickly volatile situation. He kept in constant correspondence with his superiors in the British government, his family members remaining in urban Charles Town, and increasingly hostile Patriot authorities. Whig leaders–and in particular, Henry Laurens– not only resented the British vessels for their obstinate presence in the harbor, but also blamed the vessels’ commanders for a variety of alleged social and criminal transgressions, including protecting bandits and encouraging the escapes of enslaved Africans from planters around the Lowcountry. 11

Much of that heated exchange between Captain Edward Thornbrough and Henry Laurens was published openly for the general public in the 7 November 1775 edition of the South-Carolina Gazette and Country Journal. Laurens warned Thornbrough that a “Negro Man named Shadwell, a Mariner by Profession, the Property of John Allen Walter, Esq.; is employed…under your command” and demanded his return to Charles Town. Thornbrough responded that he would shut down all commerce in the harbor if one of his own men wasn’t released by the American “Villains.” The correspondents also debated the truth of whether Campbell and Thornbrough had forcefully taken over a Rhode Island sloop, and whether or not Campbell was seeking military reinforcements from Loyalist-aligned St. Augustine, Florida. In fact, only a couple of days after the publication of these letters, news arrived that a Royal Nay schooner, St. Lawrence, had been sent by British officials in Boston (then under siege by American forces led by George Washington) to assist Thornbrough. 12

Far from being limited to local affairs, the debates and developments of those few days in early November reveal the growing chasm that had emerged between American and British leaders throughout the colonies by the end of 1775. Tensions between Whig leaders in Charles Town on the one hand, and Captain Thornbrough and Lord Campbell on the other, were intimately connected to the simultaneous (and better-known) battle for Boston. One can almost imagine citizens in Charles Town gathering by warm hearths in local taverns, reading those foregoing letters, and debating over what would happen next! 13

The Engagement

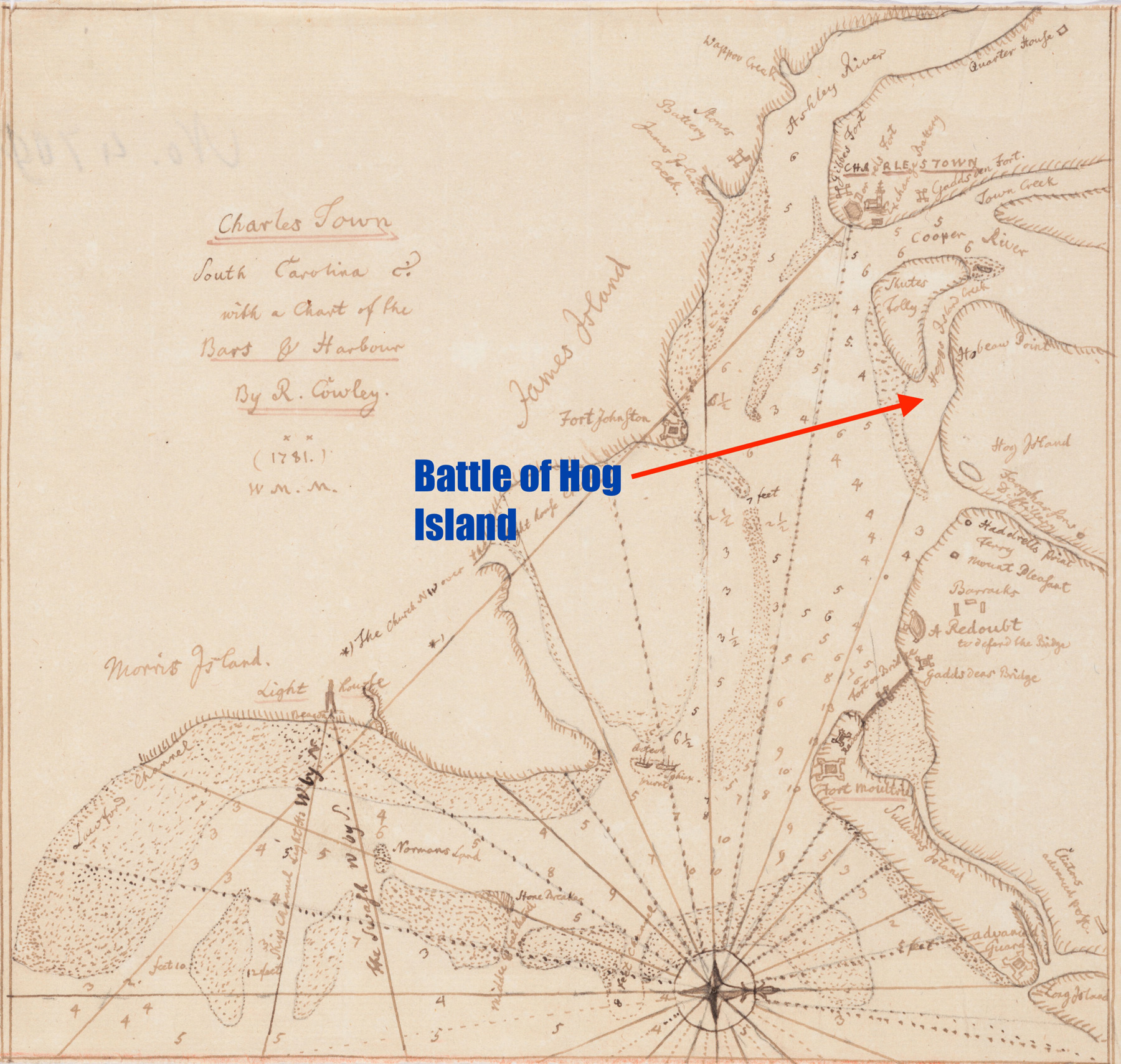

The impending arrival of St. Lawrence provides the immediate context for the Battle of Hog Island Creek. As early as October, the president of the Provincial Congress, William Henry Drayton, and his colleague Thomas Heyward, Jr. had made plans to obstruct this creek–more appropriately called a channel–between Hog and Shutes Folly Islands. They realized that three British warships could easily use the sheltered channel to enter the heart of Charles Town harbor and bombard the city, all the while evading the gun range of American-held Fort Johnson to the southwest. On 10 November, Drayton reversed previous orders to Tufts to patrol near Wappoo Creek to the west of Charles Town, and ordered him to lead his crew–along with a detachment of infantrymen acting as marines sent by Colonel William Moultrie–to oversee the sinking of various hulks in Hog Island Creek.

Unsurprisingly, American and British sources tell widely different stories of what happened next. Drayton, who volunteered to personally accompany the mission, reported that as Tufts’s men began to sink hulks with heavy loads of sand on 11 November, Tamar sailed close and fired a series of salvos at Defence. Captain Tufts ordered his men to return fire a few times, but tried to keep them focused on their original task of obstructing the creek. Although his men “accordingly sank three large scooner [sic] hulks,” the fourth was delayed by the tide, and Tufts chose to remain on station throughout the night to finish the task.

Between 4:00 and 7:00 in the morning of 12 November, Tamar and Cherokee, “on board of which last, Lord William Campbell has for some time past fixed his residence,” both bore down on Defence, and fired several broadsides at the small schooner. Drayton extolled Tufts’s bravery, who, “notwithstanding so heavy a fire,” refused to retreat until the last hulk was scuttled. Unfortunately, as soon as the schooner fell back from this final task, an armed British boat crew seized the last schooner and burnt it before it fully sank.

Throughout the heated engagement, Drayton noted the miraculous lack of any American casualties and recorded only limited structural damage on Defence (“…one shot under his counter, one in his broadside, and a third which cut his fore starboard shroud” ). Drayton maintained that “the officers and men on board, although in general new in the service, displayed the greatest chearfulness [sic], tranquility and coolness during the heavy fire.” He also recorded that while the engagement occurred on the water, gunners at Fort Johnson fired a few ineffectual shots at the British vessels, the local militia assembled in urban Charles Town, and the “inhabitants of this metropolis were in general spectators of the latter part of the cannonade.” 14

Thornbrough’s summary was obviously much less laudatory. In his logbook entry for 11 November, Thornbrough recorded “Little wind and Clear…at 4 PM came down hog Island Creek a large Schooner with 14 Guns Manned with rebells to Protect…three Old Vessels to sink some w[h]ere in the Harbour…” At 4:30, Thornbrough ordered his men to fire a single shot at an American boat that was taking sounding measurements. In response, Defence “fired 4 Shott at us and we [returned] Several at them but fell short on boath Sides.” In his entry for 12 November, Thornbrough maintained that Tamar’s and Cherokee’s early morning fire was so heavy that it forced Tufts to retreat to Charles Town. 15

While Drayton maintained that the engagement was a glorious show of perseverance in the wake of heavy British cannonading, Thornbrough dismissed the efforts of the Defence crew, and implied that they fled before the heavy guns of his small fleet. Despite these vastly different accounts of the engagement, both men would likely have agreed on one thing: the die had been cast and a proverbial rubicon had been crossed. South Carolina Revolutionaries and British forces were now not only engaging in a war of words, but in open battle.

Aftermaths

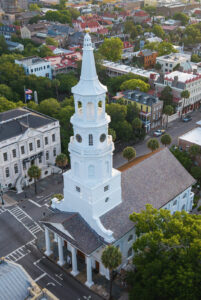

It seems that Whigs in Charles Town shared Drayton’s enthusiasm. Historian Harold Mouzon remarks that “…Mr. Drayton came triumphantly ashore amid the plaudits of the spectators…It was Sunday and there was a jubilant service in St. Michael’s with the Protestant equivalent of a Te Deum, after which the Provincial Congress met and publicly thanked” the officers and men. By the end of the month, locals finished the original mission of obstructing the harbor.

Unfortunately, whatever post-battle pride locals had would be tempered by organizational drama and infighting typical of all military organizations throughout history. Though the Provincial Congress rewarded Tufts by placing him in command of the newly-commissioned warship Prosper, they quickly reversed their decision and gave command of the well-armed vessel to one of their own–William Henry Drayton. Tufts acquiesced to this political favoritism without much complaint and returned to his command of Defence. Drayton, who had no maritime experience whatsoever, eventually resigned his command to take a position as chief justice of the state in early 1776. 16

Though light in casualties and immediate strategic results, the Battle of Hog Island Creek’s legacy is significant for several reasons. First and foremost, the battle encouraged the colony’s legislature to expand its naval establishment (which would be streamlined and given a permanent administrative apparatus with a few months later with the adoption of the state constitution of 1776).17 Following the career of Defence even after the guns fell silent on 12 November also gives us a chance to appreciate the diverse array of individuals who made the South Carolina State Navy possible. Take for instance the petition of “John Featherston, a Free Negro man…That…served on Board the Schooner Defense…for the Space of Seven Months,” and who successfully campaigned for backpay for his service despite resistance from Captain Tufts.18 Or consider the example of the Betsy-Ross-like figure Ann Holmes, who was paid £37 by the state’s naval commissioners for “mak[in]g Colours for the Defence.” It is quite possible that the schooner’s flag was the same blue banner with a white crescent that would be popularized during the Battle of Fort Moultrie. 19

Ultimately, the records of this diverse cast of characters “behind-the-scenes” is what makes the story of the Battle of Hog Island, and the subsequent maritime engagements along South Carolina’s coast so compelling. Commemorating this engagement–and the subsequent seven years of maritime battles throughout our state–not only sheds light on the oft-ignored maritime theatre of South Carolina’s Revolutionary experience, but reminds us of the continued importance of the sea to our state in the present day. It is no coincidence that Charleston serves as one of the largest container shipping ports in our nation, or that both the U.S. Navy and U.S. Coast Guard alike maintain an active presence in the Palmetto State. Perhaps the most ironic legacy of the Battle of Hog Island, and one that would certainly have amused William Henry Drayton himself, is the presence of the WWII aircraft carrier U.S.S. Yorktown and destroyer U.S.S. Laffey on the site of that maritime skirmish!

Footnotes

- William Henry Drayton to the Georgia Council of Safety, 12 November 1775, in William Bell Clark, ed., Naval Documents of the American Revolution, Volume 2, (Washington, D.C.: Naval History Division, 1966), 1004

- “Papers of the First Council of Safety of the Revolutionary Party in South Carolina, June-November, 1775 (Continued).” The South Carolina Historical and Genealogical Magazine Vol. 1, no. 1 (1900): 41–75. Jstor, Harold A. Mouzon, “Defence, a Vessel of the Navy of South Carolina,” The American Neptune, Vol. XIII, No. I (1953), 29, and Nic Butler, “The Rebellion of South Carolina: April 21st, 1775,” Charleston Time Machine Podcast, 4 May 2018, Charleston County Public Library. https://www.ccpl.org/charleston-time-machine/rebellion-south-carolina-april-21st-1775

- For more on South Carolina’s colonial militia, see Theodore Harry Jabbs, “The South Carolina Colonial Militia, 1663–1733,” Ph.D. diss., University of North Carolina, 1973. For more on South Carolina’s colonial navies, see Benjamin Schaffer, The First Fleets: Colonial Navies of the British Atlantic World, 1630-1775 (University of Alabama Press, 2025), and “Pirates, Politics, and Provincial Navies: Colonial South Carolina and its Naval Forces, 1700-1719,” The South Carolina Historical Magazine, Vol. 122, No. 2 (April 2021), 60-87.

- Charles Oscar Paullin, The Navy of the American Revolution: Its Administration, Its Policy and Its Achievements(Burrows Brothers Company, 1906), 418-419. For the most recent treatment of these early missions, see Rob Shenck, “The Birth of South Carolina’s Navy-1775,” SC 250 Commission. https://sc.stg.lazarushost.com/scnavy/

- Mouzon, “Defence,” 29

- “British Survey Vessel ‘Cherokee’ (1774),” Three Decks Database. This database draws on a variety of primary sources, and frequently draws on Rif Winfield’s extensive book British Warships in the Age of Sail, 1714-1792 (Seaforth Publishing, 2007). https://threedecks.org/index.php?display_type=show_ship&id=7566

- For more on these fascinating vessels, see Ian McLaughlan, The Sloop of War: 1650-1763 (Seaforth Publishing, 2014). Also see “British Sloop ‘Tamar’ (1758),” Three Decks Database https://threedecks.org/index.php?display_type=show_ship&id=7061

- Mouzon, “Defence,” 30.

- P.C. Coker, Charleston’s Maritime Heritage, 1670-1865: An Illustrated History (Cokercraft, 1987), xiii-xv,

- Mouzon, “Defence,” 32. For a sample of sources covering Tuft’s extensive maritime and mercantile background, see The South-Carolina Gazette Issues from 16 March 1752, April 1768, 4 September 1762, and 4 April 1768.

- William J. Harris. The Hanging of Thomas Jeremiah : A Free Black Man’s Encounter with Liberty (New Haven: Yale University Press, 2009), 153. ProQuest Ebook Central.

- The South-Carolina Gazette; and Country Journal, Tuesday, 7 November 1775, and Journal of the South Carolina Provincial Congress, 9 November 1775, in Crawford, ed. Naval Documents, Vol. 2, 962. For more on the Siege of Boston, see Woody Holton, “Chapter 17: Freedom Hath Been Hunted Early: 1776,” in Liberty Is Sweet : The Hidden History of the American Revolution, (New York: Simon & Schuster, 2021), EbscoHost eBook.

- Mouzon, “Defence,” 30-31, and Nic Butler, “Hog Island to Patriots Point: A Brief History,” Charleston Time Machine Podcast. Charleston County Public Library. https://www.ccpl.org/charleston-time-machine/hog-island-patriots-point-brief-history#_edn13

- Drayton to the Georgia Council of Safety, 12 November 1775 in Clark, ed., Naval Documents Volume 2, 1004-1005.

- “Journal of H.M. Sloop Tamar, Captain Edward Thornbrough,” in Clark, ed. Naval Documents, Vol. 2, 1015-1016

- Mouzon, “Defence,” 32-33, and “The Ship ‘Prosper,’ 1775-1776.” The South Carolina Historical Magazine, Vol. 59, no. 1 (1958): 1–10.

- Paullin, Navy, 420-422.

- South Carolina Audited Accounts relating to John Featherston [Fedderson] SC2902, Southern Campaigns American Revolution Pension Statements & Rosters, Transc. by Will Graves https://revwarapps.org/sc2902.pdf. There were a number of other Black mariners on Defense. See P.M. Hinton and John L. Marker, Jr., “South Carolina Free Men of Color in the American Revolution,” SC 250 Commission. https://southcarolina250.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/08/A-A-Soldiers-List-9.1.2020.pdf

- A.S. Salley, Jr., Ed. Journal of the Commissioners of the Navy of South Carolina: October 9, 1776-March 1, 1779 (Columbia: The State Company, 1912), 34, and Peter Anson, “Flags of the State Navies in the Revolutionary War: A Critical Overview,” Raven: A Journal of Vexillology, Vol. 17 (2010), p.

_________________________________

Benjamin Schaffer is a historian of early American history, with a special focus on maritime conflict and society in the British Atlantic world of the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries. He has a Ph.D. In early American/Atlantic-world history from the University of New Hampshire (2021). His doctoral research inspired his first book (which is set to be published in early 2025 with the University of Alabama Press): The First Fleets: Colonial Navies of the British Atlantic World, 1630-1775. This book investigates how Anglo-American naval efforts against European, piratical, and Indigenous maritime threats informed the development of the American naval tradition on the eve of the American Revolution. In addition to this book, he has published work at The Northern Mariner and The South Carolina Historical Magazine.